Building a More Equitable Digital World: Kevin Andrews Brings Accessibility Message, Strategies to UVA

In today’s society, it’s easy to take for granted how many aspects of our lives are dependent on websites and digital tools.

They are how we do our work, manage our finances, and stay connected with family and friends — as well as perform countless other everyday tasks, some trivial, some vital.

But for millions of people with disabilities, this is a world that is too often difficult to explore or, worse, sometimes closed off altogether.

Kevin Andrews, who is blind, knows all too well the challenges of navigating an electronic world riddled with barriers. For him, digital accessibility is not just about maximizing a website’s performance — it’s a moral imperative.

“You have a moral, ethical obligation of just being decent to other people,” Andrews told a recent gathering at the University of Virginia of web editors, communicators, and other higher education professionals interested in learning how to promote a more equitable digital landscape.

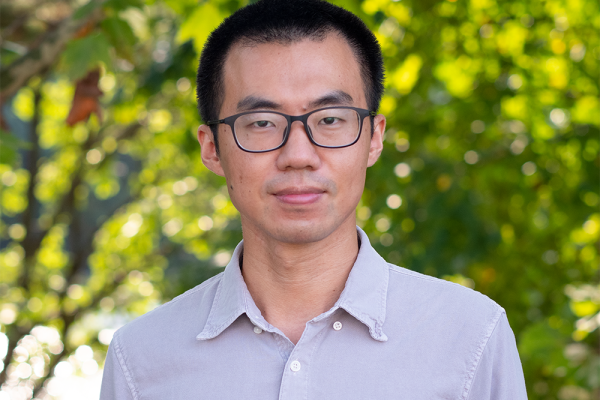

Andrews is the founder of Unlocked Freedom Access, a consulting firm committed to the notion that digital accessibility is a fundamental human right. He is a longtime accessibility expert and advocate, working previously for the University of California, Santa Cruz in that area; since 2019 he has served as the electronic IT accessibility coordinator at Georgetown University.

Over the course of a recent 90-minute presentation at UVA, which was sponsored by the School of Data Science, the Office of the Vice President and Provost, and University Communications, Andrews discussed a wide range of topics related to digital accessibility and how society can move closer to achieving it.

Approximately 1 in 4 adults in the United States have some type of disability, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, such as vision difficulties, hearing loss, or mobility problems.

There are many different types of accessibility measures to assist people with disabilities, Andrews explained, some of which are helpful to anyone, such as auditory announcements at transit stations and elevators.

“Accessibility is not just for people with a disability; it benefits everyone,” he said.

There are also more technical accessibility tools, Andrews said, which are critically important to millions of people with disabilities. These tools include assistive technology, which he defined as any equipment, software, or product that can be “used to increase, maintain, or improve the functional capabilities of persons with disabilities.” This technology can be as simple as pencil grips or as complex as text readers and speech-generating devices.

One challenge for many people with disabilities, though, is the significant cost of some of the more advanced assistive technology tools.

“There are a lot of barriers for folks to even obtain them. It’s very expensive, very cost prohibitive for a lot of people, which can make access to employment and access to academics very challenging,” Andrews said.

He illustrated how screen readers work for those in attendance and why simply having a technologically advanced tool is not sufficient to ensure a person with a disability can logically navigate a website.

For instance, he demonstrated to the audience how, if poorly phrased, hyperlinked text might be inscrutable to a person with a disability.

“So, you’re seeing that the screen reader moves sequentially through the page, which is why it’s really important to consider your link text,” he said, noting how hyperlinked text such as “click here” will mean little to someone listening to this command through this format.

Instead, he explained, link text should provide concise, descriptive context about where a user would be sent to if the link is clicked.

Andrews also discussed how headings are used by screen readers to allow users to skim through a website and understand its content through keyboard interactions rather than a mouse.

“The reason we want things like headings and good link text is so you can jump to sections of the page,” he said.

Adding alternative text, commonly known as alt text, to visuals is also key as it allows users to understand the purpose of an image without seeing it. But, he emphasized, this text should not be “super long,” joking that a picture, as the old saying goes, is not really worth a thousand words of alt text.

“Don’t do it. No one is going to listen to that,” he said.

For colors on websites, Andrews emphasized the importance of contrast: “Sufficient color contrast really helps those with low vision, are colorblind, or even those with near-perfect vision who may be impacted by environmental factors."

When assessing whether a website is accessible, Andrews encouraged web developers and editors to solicit input from the people who are consuming their content.

“Your most powerful reviews sometimes you get from your users,” he said, adding that the stakes for higher education digital communicators could be particularly high. “If people want to apply to UVA and they can’t because it’s not accessible, they can’t fill out the form, they probably go somewhere else, right?”

As for where the digital accessibility landscape may be headed, Andrews touched on the potential of artificial intelligence to bolster these efforts. While he noted that AI has already “significantly enhanced accessibility,” he issued a cautionary note that AI systems need to be developed in ways that avoid reinforcing biases, ensure data privacy, and promote equitable access.

“So, nothing about us without us,” he said. “Those for whom it’s going to have an impact, they need to have a say in how it’s going to be designed and what’s going to happen and how the data is going to be used.”

Wrapping up his remarks, Andrews acknowledged that there was not a “one-size-fits-all approach” to ensuring digital accessibility and that no one should take a critique of their website personally, noting that “people just want to access stuff.”

“Just because you came here today, that’s great, but now go out and do it,” Andrews exhorted the audience.