Aaron Martin on Digital Identity, the Orb, and the Future of Biometric Technology

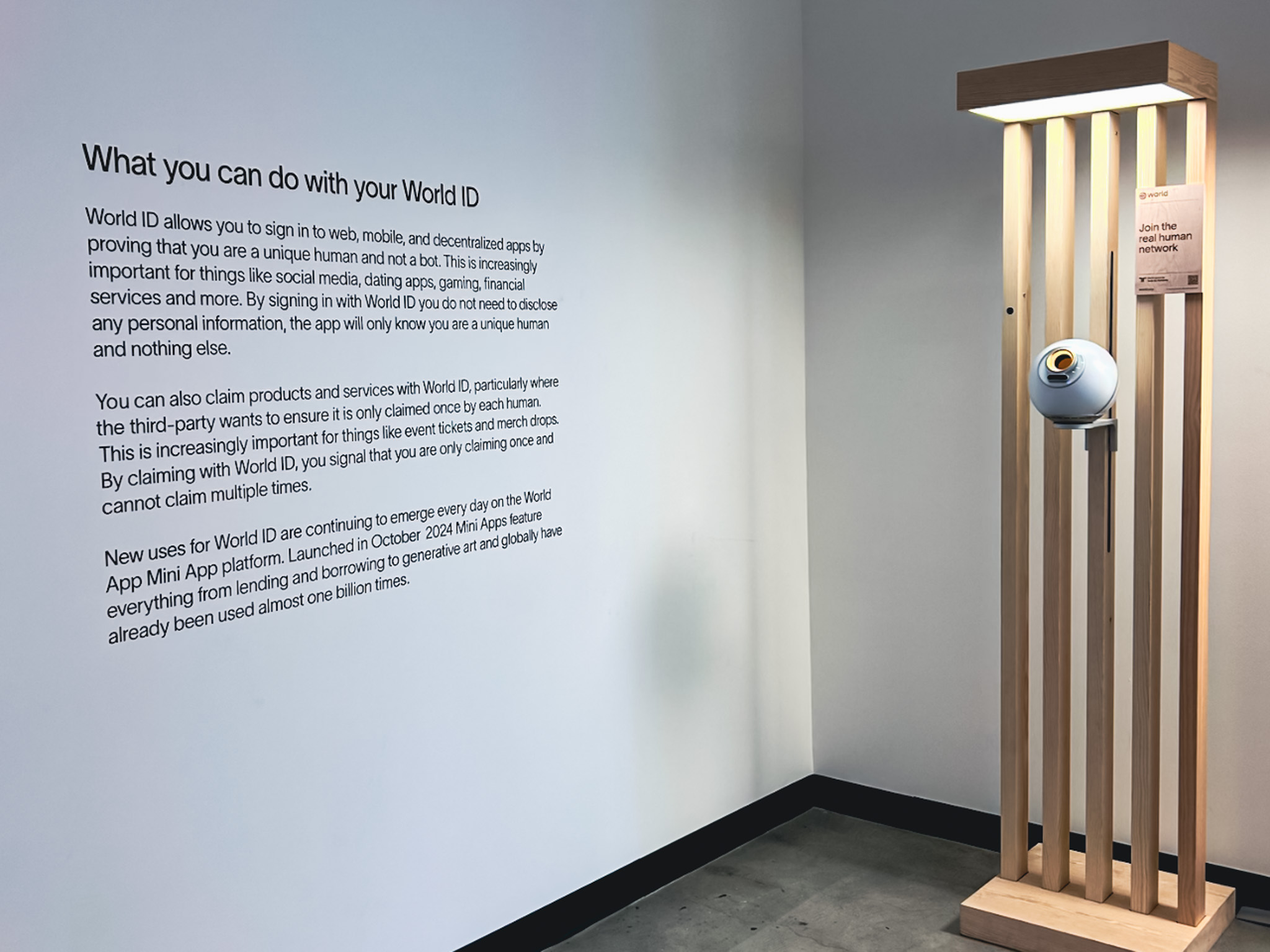

Tools for Humanity, co-founded by the CEO of OpenAI, graced the recent cover of Time magazine with the Orb — a sleek, spherical device that scans and maps your iris, providing a unique binary number that discerns man from machine in our evolving digital spaces. We spoke with Aaron Martin, assistant professor of data science and media studies at the University of Virginia, about the Orb and other forms of biometric technology that promise our online safety yet threaten the security and ownership of our personal data.

Q: What is biometric technology and how might people already be familiar with it?

A: Biometrics have a long history. Fingerprinting, for example, was originally developed in colonial settings like India, where the British used the technology to try to control the local population.

Most of us will be familiar with forensics applications for biometrics in law enforcement and judicial contexts, including the use of fingerprints and more advanced technologies like DNA. Scholars have even written about the “CSI effect” and how it shapes our perceptions and expectations about these methods.

Facial recognition and other biometric technologies are increasingly being commercialized for security and authentication purposes. Despite public resistance, authorities all over the world are deploying video surveillance systems enabled with automatic facial recognition. Some folks even pay handsome sums of money for the privilege to have their irises scanned in airports to be able to bypass long security lines. And most of us don’t think twice before scanning our face or fingerprint to unlock our phones. This is all biometrics. The technology has become part of our everyday lives.

Q: TIME’s recent cover story features Tools for Humanity’s iris-scanning Orb, promoted as an open-source, privacy-preserving technology. What concerns does the Orb present to our future, and in what ways could it be a necessity?

A: The company behind the shiny orbs does a great job of marketing its technology. You’ve just mentioned the open-source and privacy dimensions that they’re keen to advertise, which are important design considerations. We don’t want sensitive biometric data to be inappropriately collected or insecurely processed.

However, I’m more concerned about the introduction of digital identity infrastructures by private companies whose values aren’t necessarily aligned with the public interest. Especially where their technologies are meant to perform important public functions like mediating access to basic rights or services. In some places, for example, a biometric scan is required for people to access basic food aid. That makes our technology choices incredibly important. As these digital identity systems become increasingly essential to our lives, we must carefully consider how they’re being developed and governed.

What’s especially ironic about World is that it purports to be the solution to the “bot problem,” i.e., that online it’s getting harder and harder to tell if we’re interacting with a real human or AI. But the company’s co-founder is also the CEO of OpenAI, the company largely responsible for unleashing generative AI tools onto the world and getting us in this situation in the first place. Why should we trust such opportunists?

Q: If companies like Tools for Humanity continue to develop this technology, what do you imagine our lives could look like 20 years from now?

A: I think it’s important to emphasize that it’s not a foregone conclusion that these “solutions” will ever be mainstreamed, at least not in the way that their backers hope. There’s already been considerable resistance to the company’s biometric data collection practices outside the U.S., including by privacy regulators and data protection authorities in places like Kenya, Argentina, and Hong Kong. I expect this regulatory pushback to continue, which will make it more difficult for any of this to scale.

However, there’s another possible scenario: a society in which we find ourselves dependent on a private company’s digital identity technology to prove not just who we are but also that we are actually human (what they call “proof of personhood”). As my collaborator Keren Weitzberg and I argue in our essay in the Reimagining AI collection, this would be problematic for different reasons. One of those reasons has become very apparent this week. There are real risks that follow from our growing dependence on technology and infrastructure provided by private actors. Just ask NASA or the Department of Defense about the future of their SpaceX investments following the end of a certain high-profile bromance.

Q: Are there any alternatives to biometric technology that could be adopted, or greater precautions companies should take when implementing it into our everyday lives?

A: To be clear, I don’t think the use of biometrics is necessarily a problem. These technologies will have an important role to play in our digital environments, and their appropriateness will depend on different factors. For example, my colleagues and I have written about the potential for biometrics in humanitarian aid particularly in giving people who otherwise lack a legal identity some form of recognized identification, which in some respects is World’s value proposition.

The problem, however, is that for these identities to have any value, they must be recognized by government authorities and other parties. To date, this hasn’t proven to be an area in which the state has been willing to delegate much responsibility. Legal identity is still very much state business. And at least in the U.S., where we lack anything resembling a national digital identity infrastructure, we’re left with a patchwork of drivers’ licenses, data brokers, and companies like Apple and Google and their wallet technology. This is where Tools for Humanity and its competitors see opportunity.

However, if you look elsewhere such as in the EU, you’ll find that they’re developing new identity infrastructures in order to strengthen their digital sovereignty. The private sector will play a role in this initiative, but everything is taking place under the auspices of public governance.

Q: How can we protect and preserve our sense of personhood as our individual data becomes increasingly intertwined with digital spaces?

A: This won’t be easy. It will require a combination of things. We need better laws and regulation that protect our data and give us rights over it, with effective enforcement. We need increased public awareness about what’s at stake if we don’t buttress our digital ecosystems — this spans concerns about AI, digital identity, exploitative business models, and more. And while this may be an unexpected remark from someone at the School of Data Science, I think we also need to consider demarcating some aspects of human life from digitalization. This is different from the “techlash.” It’s about trying to preserve some of our human autonomy in a world where datafication is happening everywhere, in ways that feel more and more uncontrollable.

Q: Where can people follow your work and stay up-to-date with your research?

A: That question is harder to answer than it used to be! With social media degenerating lately, I’m reluctant to recommend any specific site or platform anymore. To its credit, Bluesky is trying to “billionaire-proof” its platform, so you can find me there for now.

And if you’re a UVA student, you can always come to office hours. There’s no better way to verify your humanity than by checking in with your professor in person.

You can read Aaron Martin's and Keren Weitzberg's essay, "Verified Human? Identity Inversions in Our New Machine Age," here.

A social scientist specializing in technology policy and data governance, Aaron Martin studies how regulation can facilitate just, inclusive, and secure digital societies. In addition to focusing on how transnational policy is established by international bodies and humanitarian organizations, he explores how users in historically marginalized communities, including refugees and other vulnerable people, understand and shape technology and its regulation.

Martin's work has appeared in Big Data & Society, Law, Innovation and Technology, IEEE Privacy & Security, Telecommunications Policy, Global Policy, and Geopolitics, and has been featured in media venues like The Economist. His research has been funded by the European Commission, UN Refugee Agency, European AI & Society Fund, Luminate, European Parliament, and Robert Bosch Foundation.

Martin received his Ph.D. in information systems and innovation from the London School of Economics and Political Science. He was a postdoctoral research fellow at the Tilburg Institute for Law, Technology, and Society in the Netherlands (2018-23), and before moving to UVA, he led Maastricht University’s Humanitarian Action Program in partnership with the International Committee of the Red Cross. He has held tech policy positions at JPMorgan Chase and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

In addition to serving on the faculty of the School of Data Science, Martin holds a joint appointment in the Department of Media Studies.