Caitlin Wylie's Open-Access Book Examines the Intersection of Fossil Preparation and Data Collection

What makes good data? How is data prepared and who gets to decide what counts as data? Have you ever thought about dinosaur fossils as data?

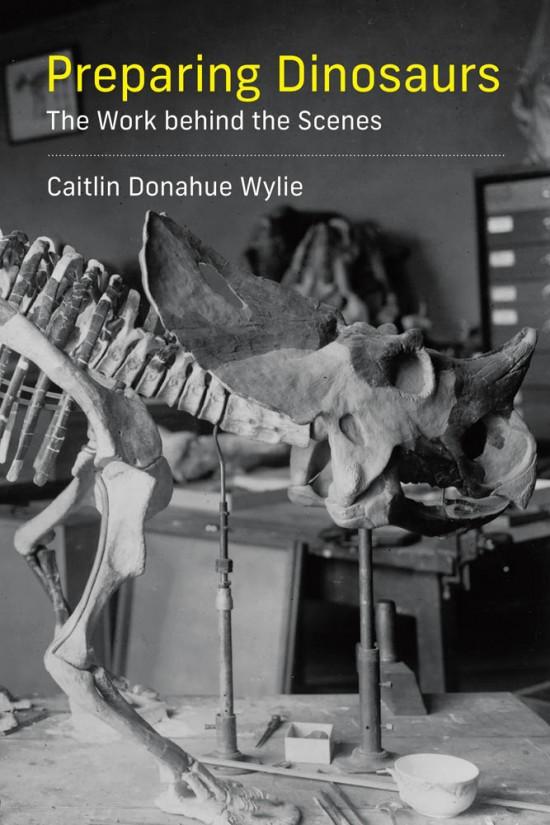

Caitlin Wylie, Assistant Professor at the School of Engineering and Applied Science and who holds a courtesy appointment with SDS, applied these questions to the study of dinosaur fossils in her book Preparing Dinosaurs.

“A fossil buried in the ground is not data, because it can’t be studied,” she noted. “But all the work and people required to make that fossil researchable is hidden from publications and exhibits, in part because scientists don’t do it, technicians do.”

Data often needs to be cleaned by data scientists before it is usable, and that applies to dinosaur fossils too. This means that data scientists, or in this case fossil technicians, make decisions regarding which numbers to keep in a set, what is misformatted, what is problematic, and what gets deleted. Then, with the clean data, data scientists can analyze and study what the numbers mean. Wylie draws a parallel to preparing fossils and explains how preparing these bones is a form of data processing.

“The work these technicians do is crucial, yet often forgotten,” explains Wylie. “They are adapting methods and setting requirements for what makes a good fossil.”

For example, in the first chapter of the book, Wylie wrote about a fossil preparator Jay at the Southern Museum. Jay reconstructed fossil fragments using distinct techniques and often tinkering with different methods. For example, hematched loose bone pieces together, rebuilt a shattered skull, and designed a unique storage container to protect a prepared fossil.

“Preparing evidence, then, involves deciding what materials and/or observations are relevant, what form they should take (e.g., physical appearance and organization), and how to achieve that form,” Wylie writes in her book. “These decisions often fall to individual practitioners [like Jay], who make in-the-moment judgments based on their expert observations and then apply skillful actions to pursue their expectations of the evidence. Diversity in individuals’ preferences, skills, and priorities, including judgments of what is beautiful, results in a variety of possible forms that a single piece of evidence can take. It is therefore crucial to study the factors that influence how those possible forms take shape.” (Preparing Dinosaurs, p. 28).

Just as data scientists decide what numbers to keep in a data set, fossil preparators decide what type of plaster to use to best make a cast for a particular bone, which pieces to glue when rebuilding a skeleton, and if their techniques are reversible or not.

“It's a story about the division of labor and science,” Wylie describes her book released on August 31. “This is a story about ethical practice in science. I’m looking at a particular group of science technicians, fossil preparators, who I believe can teach us a lot about what it means to generate good data.”

Wylie’s interest in fossils and science began while an undergraduate student at the University of Chicago where she worked in a fossil lab.

“My job was to scrape tiny bits of rock off of the fossils, glue broken bones together, and make sure I didn't hurt the specimen,” Wylie said.

Wylie was especially fascinated by the professional fossil preparators in her lab, who trained her and spend their lives doing this kind of work. “They are amazing. They can transform this chunk of nothing into a gorgeous bone, skull, or skeleton, that can then be studied and exhibited.”

Wylie decided to study abroad in London and continue preparing fossils at the city’s Natural History Museum.

However, when Wylie began working at the Natural History Museum, she soon discovered something that was a complete surprise. The fossil preparators at the Natural History Museum had a different method for fossil preparation than those who had taught her at the University of Chicago.

“I was amazed that fossils could be prepared in such different ways, yet the end results were still studied and compared in the same ways.”

This led Wylie to ask the question: What is the right way to prepare a dinosaur fossil?

“I got suspicious,” Wylie explained. “How can we pursue scientific knowledge about objects that have been prepared as data in different ways?”

This inspired Wylie’s graduate work and dissertation and, ultimately, her new book. Wylie has continued researching fossil preparators, alongside academic teaching at different universities, since 2013.

During her research, Wylie visited 14 labs in three countries to observe fossil preparation methods. She found, again and again, differing techniques in fossil preparation, yet there was also a common thread. These fossil preparators and their diverse methods are largely unknown.

“A lot of the crucial work in science that goes into making data usable is done by people who are not scientists, people whose names and work are not published or publicly known,” Wylie explained. “I am thrilled that my book attempts to recognize the work of the many fossil preparators who were kind enough to talk to me and show me their labs. My hope is to draw public attention to their amazing work.”

Throughout her many years working in and researching fossil preparation labs, Wylie has been fascinated by the creativity, craft, and problem solving skills preparators possess.

Wylie’s motivation to recognize this often overlooked group of technicians, and other experts like them, reflects herbroader commitment to ethical data science that celebrates all the work and workers who make research possible.

Want to read about fossil preparators and the data they collect? Preparing Dinosaurs is open access and anyone can read it for free. Learn more